The Historical ipa mixedpack no.1

For the first time, a series of historical IPAs from different periods in history are all available in a single pack. You can order these online here. I’ve taken a deep dive into the history of IPA and resurfaced with historically accurate re-creations of IPAs from the years 1754, 1823, 1870 and 1914 to bring you a taste of early versions of this legendary style. These are important years in the life of IPA, and this is their story. While there’s no one on earth old enough to compare these ales to the originals, I think they’re close. But judge for yourself. Here’s what I did for each ale:

Re-created the water chemistry as it was in each place and time when these ales were brewed by adding the appropriate minerals and salts.

Re-created or followed the original recipes as they appear in the historical record.

Fermented with a blend of heritage English yeast strains.

Grew and dried my own hops to make test batches that compared the potency of this more traditional, manual method of hops processing with contemporary industrial practices and adjusted the recipes accordingly

Aged the ales representing the years 1754 and 1823 for months in oak barrels in a hot warehouse to simulate the trip to India.

Added Brettanomyces claussenii to the barrel aged ales post-fermentation (more on this below).

Carbonated the ales by re-fermenting them in the can rather than force-carbonating with CO2.

Sourced contemporary ingredients that are as close to the originals as possible.

This project has been years in the making but that’s nothing compared to the centuries it’s taken to get the style to where it is today. So listen on to dive into the world of IPA.

Check out the labels below and read on (or follow the links and listen) to dive into the world of IPA.

Listen on Spotify or Apple Podcasts

This is an approximately 40-minute read. A 90 second version is available here. If you live in British Columbia, you can order the historical IPA mixed pack online here.

Introduction to the origin of IPA

IPA is the result of a lucky mix of business deals, global wars, unknown microbes, and cultural forces. This article tells the story of its first life, as it rose and fell with the British Empire during the period from roughly 1750 to 1930. IPA would nearly disappear during the mid-20th century before coming back during the craft beer boom, but that’s a story for another time.

History is full of stories of hard-working geniuses whose ingenuity took them on a journey from idea to breakthrough. This is not one of those stories. Most of them aren’t even true, or at least contain as much myth as fact. Like many stories about inventions, this is a tale about how smart, hardworking, and lucky people responded to the randomness of the world as best they could and, when then found something great, held on to it.

The life of IPA began by accident at a small brewery in East London. It’s 1751. The neighbourhood is buzzing with commerce and industry, overcrowded housing, and poverty. It’s also full of breweries. One of these would link up with a global trading power that was founded to help Britain compete with France, Spain, the Netherlands and Prussia for control of global trade and military power.

The chapters are sorted by date, and each date corresponds to a ale in our mixed pack. Let’s begin.

1754: Hodgson’s accidental discovery

This is the original India Pale Ale. It was brewed in London as an extra-strong, extra-hoppy version of a pale ale but found fame in India thanks to a combination of dumb luck and good business sense. There were many English pale ales in India by the 1750s. This is the one that set IPA apart as the famous style we know today.

George Hodgson, owner of the small Bow Brewery next to the River Lea, is the accidental father of IPA. His small London brewery was just upriver from East India Company’s London docks on the River Thames. The East India Company was the largest and most powerful company in the world and was responsible for governing India. Its chairman worked as both corporate boss and governor of a large country with life and death power over his subjects.

England had been exporting ale to India since the 1600s and by the 1750s their export market had reached 1,500 barrels per year. A barrel is 115 litres. That puts the total export market to India at just over 22,000 litres per year. That’s small. Many large breweries weren’t interested in a market of that size. But it was growing fast. Hodgson wanted a piece of it.

He began offering merchant captains advanced credit to ship and sell his ales, giving them product and not asking for payment until 18 months later. That was how long a round-trip to India took on an East Indiaman, one of the lumbering cargo ships used by the East India Company. Many captains took him up on these generous credit terms and soon Hodgson was sending his ale to the other side of the world. He sent several styles at first but one of his recipes, a particularly strong and heavily hopped pale ale, not only survived the trip to India but thrived in the rough conditions that ruined most ales, and most ships.

East Indiamen were sturdy ships built for a rough voyage over stormy seas. They blended elements of merchant and warship designs so they could both transport cargo and defend against pirates. Still, the rough water, hot weather, and constant exposure to seawater degraded their hulls, riggings, and fittings. A typical East Indiaman would only make two or three round-trips before maintenance became so expensive, and operation so dangerous, that the East India Company sold them to captains who would use them for shorter trips.

The journey to India began in winter. This was when the prevailing westerly winds in the North Atlantic helped push ships down the west coast of Africa to Cape Good Hope at the continent’s southern tip. The merchant fleet sailed around the cape and into the Indian Ocean just as the southwest monsoon was beginning, in May and early June. These winds carried the East Indiamen north, over the equator and into Indian ports, and the heat for July.

It was a time when workers most needed a drink. It was also a time when year-old ale, battered by the sea voyage and wilted by a tropical summer, had degraded from a taste of home to one of homesickness.

Much of the ale that arrived in India during the early 1700s was weak, bland, and had off flavours that were stale and paper-like. One could only hope that when the ships returned the next year, the ale they carried would be better.

Ale degrades with time because heat and oxygen break down the bitter and aromatic compounds found in hops into bland and stale ones. Contemporary ale avoids this fate because of plentiful CO2, stainless steel tanks and cold-chain transportation networks. Ale was poured into air-filled wooden barrels until the 20th century, maxing oxidation the norm rather than the exception. Oxidation continued even after packaging as oxygen squeezed through the porous wood. The effect was minimal for short trips around the cool United Kingdom. It was even desirable for some extra strong ales above 10% alcohol. But the long, hot sea voyage to India ruined most ale.

This was the problem that Hodgson’s heavily hopped pale ale solved. It was so heavily hopped, at 20 grams of dried hops per litre, that by the time it arrived in India the intensely bitter ale had degraded into well balanced tipple. It was a relief. A cool pint of ale, cooled by the chemical wizardry of saltpetre, was a lot more refreshing on a sweltering summer day than a glass of brandy, sherry, or claret.

But there was more to Hodgson’s IPA than just a lot of hops. The rough, hot journey also accelerated the ale’s aging process and somehow left it tasting not only less degraded but even better than it did before it left the London docks. Somehow, the trip to India made a five-month-old pale ale taste like a strong kind of aged ale beloved by the British upper-classes whose sons made up a large proportion of the administrators in colonial India.

English breweries had been making strong pale ales throughout the 1700s. These were known interchangeably as October ale or Stock ale, because they were brewed in autumn and aged (stocked) for two years. It was a trend that began in wealthy household breweries during the 1600s. These ales could have up to 15% alcohol and spent one year in barrels and then another in bottles before they were ready to drink. They developed intense and complex flavours as they aged. Hodgson couldn’t have known it at the time but one of the ales he shipped to India, a strong pale ale, would undergo a never-before-seen change that would make it taste like a refreshing cousin of the beloved stock ale.

Hodgson’s ale seems to have benefited from a secret ingredient that thrived in warm barrels rolling on the waves. This secret was likely a microbe called Brettanomyces claussenii that was accidentally introduced into the ale via the barrels Hodgson shipped it in. Brettanomyces claussenii means “British fungus,” though it isn’t a fungus but a type of hardy yeast. And it isn’t just found in England but across the world. Brett. c. as it’s known today lives in wood just like the barrels used to ship ale, among other places. It likes warm, even hot temperatures and has the special ability to eat long chain polysaccharides that regular brewer’s yeast (saccharomyces cerevisiae) can’t digest.

It’s entirely possible that Brett. c. woke up during the hot voyage as ale sloshed within the barrels, crept out of the wood, and began to eat the remaining sugars the regular brewer’s yeast left behind. As it did it would multiply, doubling its population at a rate of up to once every ninety minutes, and impart its characteristic stock ale traits.

Written descriptions of the ale’s flavour support this idea. Although no one had yet discovered microbes, we know today that Brett. c. was common in historical English ales. Today, many people associate it with Belgian ales where it remains common. Brewers practically eliminated Brett. from English brewing after the discovery of microbes and the invention of pasteurization in the late 1800s.

Brett. c. is responsible for flavours variously described by Hodgson’s contemporaries as “old,” “stock,” and especially “farmhouse.” It would also make ale taste more “dry,” since there would be fewer residual sugars left to add the mild sweetness common in strong ales. All four of these telltale Brett. c. terms were used to describe Hodgsons’s IPA, just as they were to describe the ales brewers brewed to compete with Hodgson and the stock ales many English expats loved to drink when they were back home.

Hodgson’s pale was well loved ale. It filled the stomachs of happy expats, and the wallets of the East India captains. It turned a good profit for the merchants who sold it. It was the most popular brand in India. Hodgson’s pale ale soon became known as the East India Pale Ale. Other London breweries rushed to copy it, shipping their versions to India in the hope they could get some of Hodgson’s market share. But they had little success.

Hodgson’s early market position and generous credit terms with East India Company captains would help him gain half the of Indian export market. All this happened at a time when the Indian market was on its way to quintupling from 1,500 barrels per year in 1750 to 9,000 barrels per year by the turn of the century. During this time IPA changed from representing a taste of home to the taste of a growing empire. It was a steadfast part of a new social dynamic and developed a romantic appeal as the unofficial flavour of the expatriate experience.

Early colonial populations were overwhelmingly male. They were soldiers, labourers, traders and administrators who sought to establish and defend outposts used for strategic economic and military goals. Women began emigrating to colonies in India once the early male colonists had made them secure. They often came as the wives of officials, merchants, and military officers. Although still heavily outnumbered by men, women were central to the structure and organization of imperial social life by the late 1700s.

The role of women as social, cultural, and even diplomatic organizers and ambassadors was then an informal but critical and recognizable institution. Mixed-gender socializing was much more common in the colonies than in Britain and played a crucial role in building community and providing social and psychological support for small expatriate outposts.

Garden parties, picnics and other outdoor events were, even in the UK, mixed-gender gatherings. Weather in the UK limited social gatherings there to indoors for much of the year, where they were much more likely to be segregated. But the hot climate in India made outdoor events a common year-round occurrence. Mixed social gatherings in the colonies were also more frequent, and focused on fostering a sense of unity rather than on maintaining hierarchy. This was where women and men, military officers, civil servants, and merchants got together to reinforce their common British identity.

IPA was the flavour of these get-togethers. British expats rarely drank water. Instead, they had tea, coffee, ale, and spirits. As a refreshing alternative to tea and coffee that lacked the intoxicating power of spirits, IPA was the most popular social drink for both men and women. Men appreciated its strong, bitter flavour as masculine traits. Women found it appropriately modest because of its relatively low alcohol content when compared to spirits. It’s connection to home also helped set it apart from tea and coffee which, being imports from other colonies, lacked the patriotic symbolism of the IPA.

Hodgson’s IPA had become the flavour of social life for many among Britain’s ruling classes. His success would outlive him but this good fortune would not continue for his business. Almost seventy years after Hodgson shipped his first barrels of ale to India the new owners of his Bow Brewery, Frederik Hodgson and Thomas Drane made an ambitious business move.

In 1821 they decided to cut out the East India Company, still the largest and most powerful company in the world, so that they could ship and sell their ale themselves. They terminated their generous seventy-year-old credit terms with the East India Company captains, raised their prices by 20%, demanded cash payment up front and cut out the merchants in India who were selling their ale. The captains, the merchants and the Company were furious. They retaliated immediately.

Campbell Marjoribanks, chairman of the East India Company, began to look for a brewer who could replicate the Hodgson IPA. When he found him, he would use the massive resources of the East India Company to push the Bow Brewery out of the market with his new product. Hodgson and Drane expected this and were ready. They owned, by far, the most powerful ale brand in India. They must have anticipated this move by the East India Company and felt sure they would defeat their new rival, whoever that would be. They were wrong.

As with the Hodgson’s East India Pale Ale, the new India Pale Ale supported by the East India Company was the perfect combination of good timing and happy accidents. Within two years, in 1823, a new IPA appeared on the market that was immediately more popular and widely acclaimed as even better than theirs. Sales of Hodgson’s East India Pale Ale steadily declined over the next decade. The brewery faded into obscurity and had closed by mid-century. A new brewer had conquered the seas.

1823: Allsopp’s triumph

The 1823 IPA, known as Allsopp’s IPA or “The Burton IPA,” is the result of an unlikely meeting at a London dinner party between a struggling brewer from the centre of England and one of the most powerful merchant men in the world.

Samuel Allsopp, an ambitious twenty-seven-year-old entrepreneur acquired his uncle’s brewery in Burton-Upon-Trent in the year 1807. It cost £7,000, or about £800,000 today. His uncle’s business had started in the 1740s as private brewery in an inn serving the landlord’s customers. Its ales became so popular that the brewery began supplying other inns and by the late 1700s had become the largest brewery in Burton. Allsopp’s uncle had developed a profitable export business selling strong Burton Ale to the Baltic states but the Napoleonic Wars had cut him off from his clients and put his business in danger.

Napoleon’s Continental System, a Europe-wide trade embargo against the UK, had a major impact on Baltic trade. Allsopp’s uncle wanted out. After Great Britain won a decisive naval victory against Napoleon’s ally Denmark and captured its fleet in September 1807, the young Allsopp seems to have bet that trade with the Baltic nations would re-open. He would have to wait.

Trade remained difficult until Russia lifted its embargo in 1810, but then slowed down again when Napoleon invaded them in 1812. Export to the United States was not an option. England and France had for years been intercepting American merchant ships as each warring country tried to stop its enemy from trading with them. The United States retaliated by attempting to impose and embargo of its own that would eventually culminate in the War of 1812.

Having just spent a large sum of money on acquiring a business that had lost most of its best customers, Allsopp tried to make up his lost export sales in the domestic market. He brewed a pale ale in 1808, perhaps the first in Burton, but it must have been unremarkable because there is no record of its success and the brewery failed to grow sales as he must have hoped.

Meanwhile, the war with France was taking a toll on the public. Inflation and unemployment spiked. Protests and violence against the upper classes and industrial interests spread until the government called in solders to stamp out the unrest. It was a bad time to grow a business. Allsopp was struggling. Then, in 1822, the Russians imposed prohibitive tariffs on English ales just as trade with Russia was starting to pick back up.

All this was not Allsopp’s fault but it was his problem. He tried to solve it by expanding into the most promising market for brewers at the time, India. The brewers with the most success were those in London who were selling to India and Southeast Asia, regions that hadn’t been affected by Napoleon’s blockade, conflict with the United States, or domestic tensions. After a decade and a half of struggle Allsopp packed his bags and went to London to see if he could win some clients in the Indian trade.

The specific details of what happened next are hidden behind the veil of time. Somehow Samuel Allsopp managed to get an invitation to dinner at the home of Campbell Marjoribanks, Chairman of the East India Company. It’s unclear how he got the invitation, but if he managed to get the funds together for what amounts to an £800,000 purchase by the age of twenty-seven, he must have been well-connected. His uncle’s links to maritime trade may have helped.

What the two men discussed remains a mystery but at some point in the evening Marjoribanks produced bottles of Hodgson’s IPA. He expressed his anger at Hodgson for changing his terms so quickly and said that if anyone could replicate Hodgson’s ale, he would make him a wealthy man. Although he was in the business of making strong, sweet ales Allsopp said he could replicate it and brought some bottles back to his brewery in Burton-Upon-Trent.

Allsopp gave a bottle of Hodgson’s IPA to his brewer, Job Goodhead, and asked him if he could replicate it. It wasn’t a particularly difficult task because there were only two ingredients: pale malt and East Kent Goldings hops. The trick was getting the temperature right and keeping it there throughout the brewing and fermenting process.

We can’t be sure what happened next but the legend goes like this: Job poured himself a pint of Hodgson’s bitter ale, raised it to his lips for a sip, and then spat it out in horror. “Yes, I can make this” he is said, “But why would anyone want to drink it?” Then he brewed a test batch in his kitchen using a teapot and, finding the result similar, scaled up production to the brewery.

We can’t be sure just how it happened, but we do know that that first batch of IPA brewed by Allsopp and Goodhead was a success. Allsopp ramped up production later that year, in October 1822, and his first shipment landed in India in 1823 with support from the East India Company.

It’s not clear why Marjoribanks chose Allsopp to counter to Hodgson. There were many London breweries that were both more successful and able to brew at a higher capacity. Perhaps Allsopp, at the end of his rope after fifteen years of struggle, offered generous terms to the East India Company captains. It’s difficult to imagine a struggling brewery offering product on credit, so maybe he competed on price.

If the business case that helped get the deal across the line is uncertain to us today, one thing is clear. The ale was excellent. Better than the Hodgson’s IPA. And like Hodgson’s, the reason was a secret ingredient invisible to the naked eye. It wasn’t an undiscovered microbe but a result of millions of years of history that had produced something special deep within the earth below the brewery.

Burton-Upon-Trent sits in the Trent Valley Basin atop layers of sedimentary rocks formed during the Triassic period 250 million years ago. The water used by Burton brewers fell upon the earth as rain. It filtered through rocks tread upon by dinosaurs like Asylosaurus in the hot English prehistoric, flowed through beds of Keuper marl and gypsum, and past layers of chalk and limestone before collecting in underground springs.

When pumped back to the surface the unique mineral content of this water was ideal for brewing hoppy ales. It is rich in calcium sulfate, enhancing hop bitterness and sharpening flavour. It has high calcium carbonate and magnesium, promoting enzyme activity during the brewing process and supporting yeast metabolism during fermentation. It is also high in sodium and chloride, which are balanced in a way that brings out the sweetness in malt so that it complements the more assertive hop character.

Marjoribanks didn’t know Burton water would have this effect when he approached Allsopp. Allsopp didn’t know it when he asked Goodhead to replicate Hodgson’s IPA. But it didn’t take long for the magical properties of Burton water to transform the city into the brewing capital of the world.

Allsopp’s IPA was a success from the moment it landed in Calcutta. It certainly helped that the first shipment of Allsopp IPA landed at the same time as a spoiled shipment of Hodgson’s. But one bad shipment on its own isn’t enough to dethrone a brewery with market dominance of the kind Hodgson enjoyed. Allsopp’s product had to be consistently better, too. It was. Whether this is because Burton water changed the flavour of a virtually indistinguishable recipe is an open question. What is clear is that Burton water supported healthier yeast, and this may have resulted in cleaner, dryer fermentations that were more consistent and less likely to develop off-flavours.

Allsopp pushed Hodgson out of the Indian market throughout the 1820s and became the new dominant player in Asian market. The struggling brewer was now one of the most successful in the world.

Allsopp’s success inspired other Burton brewers to begin making their own hoppy ales. The timing was ideal. When British victory against Napoleon came in 1815 it created a period of peace and stability where Great Britain dominated the world as the only global superpower. The nation had access to an ever-increasing international market for its product through its vast network of colonies. At home, the agricultural revolution and early stages of the industrial boom that would define the 19th century were well under way. People had work, money, and wanted to buy ale. But peace at home and among empires did not mean a peaceful world.

In India, porters still unloaded cargo by hand in the thick, heavy heat of summer. They received little pay. Banyans, Indian merchants or brokers, served as a liaison between local labour and British agents. The banyans were critical for recruiting and managing a labour force that was both used to working in the hot local conditions and that could scale up during shipping seasons. But they were cut out of the lucrative export trade. British soldiers and their local equivalents hired to serve British interests, sepoys, provided security at the docks. They were paid less than their British counterparts and denied the same opportunities for promotion.

Many Indian banyans, sepoys, and upper classes had adopted British customs like enjoying a cool ale on a hot day. Although British traditions like ale caught on among many of the Indians that worked closely with them, relations between the two groups suffered from underlaying tension.

Colonial officials imposed high taxes and forced many local farmers to grow cash crops, leading to food insecurity. They caused factories to close by imposing rules that permitted only raw textile exports, rather than goods woven into value-added products. While many Indians benefited from their relationship with the British through a growing economy, improved infrastructure, and schools, many more resented a hierarchy that kept them at a disadvantage and failed to respect their culture.

A key flashpoint was the Sepoy Rebellion of 1857. It began when sepoys were issued rifle cartridges greased with cow and pig fat. The Hindu and Muslim sepoys had to bite the cartridges open, violating religious bans on eating cows and pigs.

Their commanders refused to replace the offending grease. This indignity combined with grievances about lower pay and worse working conditions to create a rebellion. The rebels received support from disgruntled farmers and textile workers but suffered from fragmented leadership and a lack of coordination. Many Indian princes continued to support the British. Though the rebellion slightly less than a year it created major changes in India.

The British Government dissolved the East India Company’s administration and took over control of region. Their response to the rebellion was a combination of reform and repression, both aimed at preventing it from happening again. But the rebellion accelerated a developing national consciousness among Indians. It would lead, in 1885, to the formation of the Indian National Congress, a political organization that became the voice of the Indian independence movement.

Though the winds of change swirled in India the monsoon winds remained the same. Cargo ships continued to arrive in July with new shipments of ale just as the hot, busy season was getting underway. Demand soared as the colonial population grew.

Production of IPA increased at a dizzying pace, particularly in Burton-Upon-Trent. The city had been an ale exporting powerhouse in the late 1700s but was a brewing backwater by the time Allsopp brewed his first IPA in 1822. There were, at that time, five breweries producing a combined total of 10,000 barrels of ale per year. That would soon change.

Brewers like Allsopp were lucky that the discovery of the magical effects of Burton water on IPA happened at the beginning of the largest economic boom in history. They also benefited from the recent invention of the coke-fired kiln, which permitted pale malt to be produced at scale for the first time. Brewery production in their city grew steadily to mid-century, then tripled every decade from 1850 to 1880. By then a single Burton brewery, Bass, was producing an annual output of over one million barrels per year on its own, and Great Britain was producing 25% of the world’s GDP.

Allsopp’s brewery continued making popular IPAs long after his death in 1838. His brewery never achieved the market dominance Hodgson enjoyed because of competition from other, larger, Burton breweries like Bass. Although he finally achieved financial success, Allsopp’s legacy is not money but the resurrection of the Burton brewing industry and a massive boost in the popularity of IPA both throughout the empire and at home. When the British Empire reached its peak in the last third of the 19th century the IPA had become the flavour of an empire.

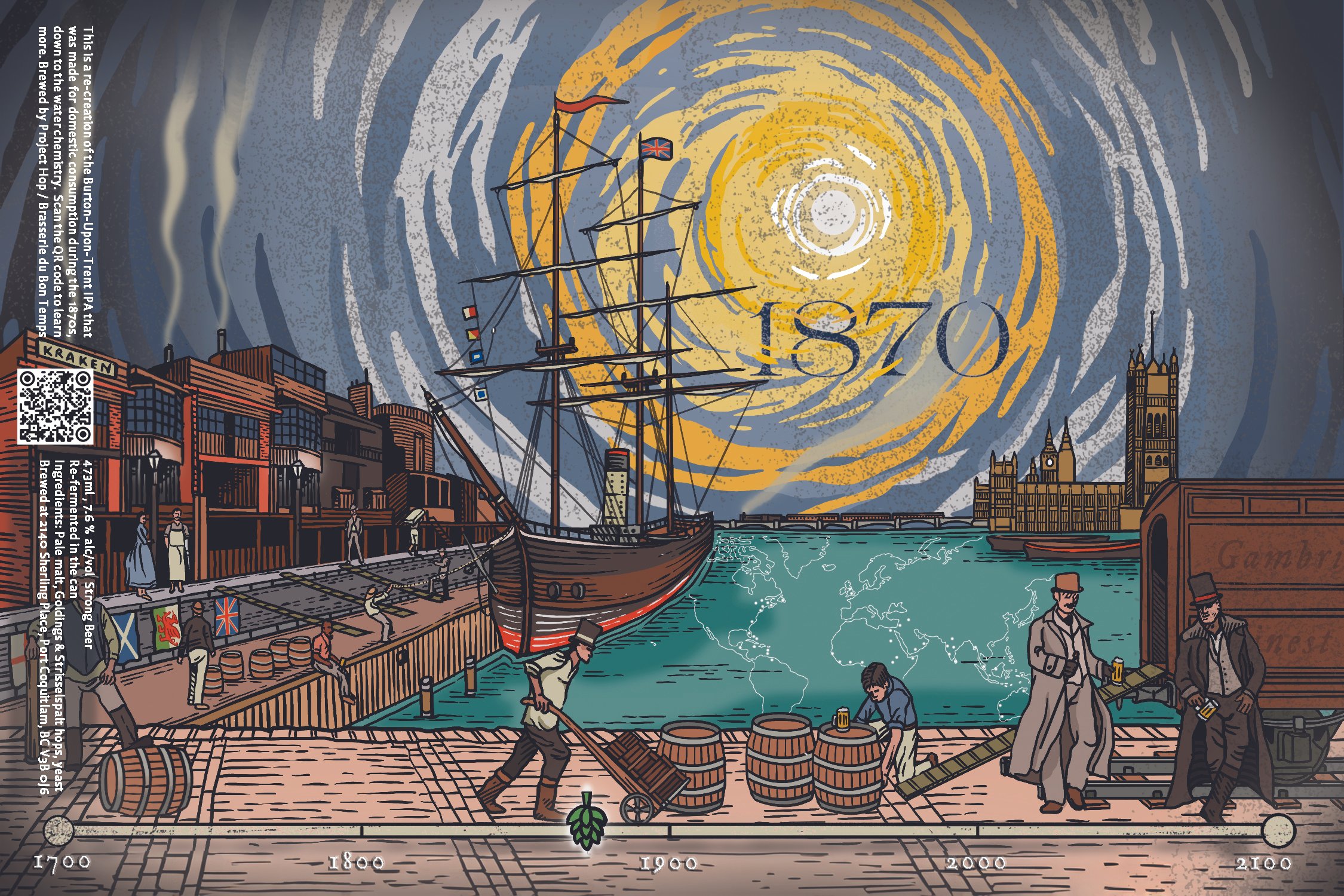

1870: The Flavour of Empire

It was a time of excitement, disruption, and progress. Wealth sailed over distant oceans, carried in the holds of the world’s largest merchant fleet. London built the world’s first subway in 1863 and within two decades the telegraph then telephone were invented along with the phonograph, typewriter, lightbulb, internal combustion engine, fountain pen, electric streetcar, camera and alternating current motor. The tide of Modernity was washing over the Old World, still visible everywhere but clearly passing away. IPA was the flavour of this new world order.

The best brewers embraced technology, boosting production, consistency, and quality for their global brands. Samuel Allsopp’s son, Henry, had modernized his brewery and increased annual production to hundreds of thousands of barrels per year. He was in fierce competition with Michael Bass, another innovative Burton brewer.

The two men were among the first to use steam power in brewing. Steam plants powered pumps and mills, elevators, and conveyors, making their breweries run more quickly and consistently as if guided by the hands of invisible workers. They built private railroad sidings connected to the national network to quickly get their products to port and around the country. Bass even used mechanical refrigeration, allowing him to brew high-quality ales year-round, and leveraged scientific brewing methods by employing chemists to study fermentation.

These advancements allowed brewers to produce far more than the export market required. And this was an export market without equal. It was the kind that allowed Michael Bass to maintain a stock of IPA that covered three floors, each two acres in size containing 30,000 barrels of ale apiece, right in the middle of London.

It was the height of the British Imperial Century. It was the peak of the Industrial Revolution. The world was enjoying the security of the Pax Britannica and the UK was the world’s largest economy and unrivaled military power. IPA was now just as popular at home as it was abroad. It represented progress and national pride. Women returning from colonial postings brought with them an appreciation for IPA and more relaxed ideas about both female alcohol consumption and participation in public life.

Women’s role in the social cohesion of the empire had grown to become more formal by the height of the Victorian period. While the predominant role of women in the empire remained domestic, including the meticulous re-creation of British households and the organization of social gatherings, some women worked outside the home.

Women now worked in formal public roles including administrative, clerical and missionary work, education, and medical care. Some become entrepreneurs running inns and small shops, others took over management of plantations, farms, and estates when the men were absent or had died. Others engaged in science and ethnography or social reform advocacy, like fighting for improved conditions for colonial workers and an end to child marriage in areas where that was common.

These opportunities for leadership combined with a growing popularity for travel literature written by British women to give them a public voice that was heard both in their expatriate communities and back home. The experiences and success of women living more independent lives than they could expect on the British Isles challenged the perception of women as suitable only for private roles. This created new expectations for women’s capabilities and helped inspire suffragettes and intellectuals to push for greater equality.

Women from the colonies, who would often have enjoyed a pint of IPA with men, were no longer willing to accept the limited and submissive roles they had left behind when they went overseas. Theirs was a new, sophisticated perspective and it provided cautious inspiration for women back home.

Ever a mirror to the society that produced it, the pale, clear appearance of IPA was by now considered a sign of sophistication when compared to hazy and dark traditional ales. This, combined with its exotic origin story, association with expanding British influence and positive change gave it the reputation as a status drink.

British GDP grew by 150% from 1840 to 1870, creating a middle class thirsty for the taste of progress. Breweries like Bass and Allsopp tailored their marketing to reinforce this message by tying their brand to their nation’s glorious rise to power and, crucially, its people’s hope for the future. To understand the difference between the way people in the UK viewed IPA and other ales all a person had to do was compare what was on tap at the pub and in the club.

The pub was the heart of the community for working-class men in Britain and ale was the blood that pumped through its veins. Pub is the short form of this institutions full name, Public House. It was a space open to anyone, although except for some rural pubs anyone did not include women. Their presence at many rural and nearly all urban pubs back home in the British Isles would be a scandal.

Working men often collected their wages at the pub, where they also settled debts, organized mutual aid societies, and held informal meetings that sometimes evolved into more structured entities like trade unions or activist groups. Pubs were also entertainment centres where men could play games like darts and billiards, creating a lively and, the later it got in the day, rowdy atmosphere.

Men gathered in pubs to unwind after long hours in factories, mines, or at the docks. Ale was viewed as a nourishing, responsible beverage for the respectable Victorian man because it contained less alcohol than spirits, but those were on offer, too. Pub goers had traditional tastes for dark ales like porter and its stronger cousin, stout, because these were seen as more nourishing than light coloured ales. Mild ales were popular, too. Their low flavour and low alcohol made them the choice ale among men who intended to drink a lot. IPA was much less common here. The high hopping rates made it expensive. For the working class, it was a patriotic drink for special occasions, if at all. IPA was not a drink for the pub, but the club.

Middle class men spent their leisure time in clubs. These were private spaces and their membership was restricted to men with similar social or professional status. Young men joined clubs to network with older men whose graces they would need for a successful middle-class career. Doctors, lawyers, and entrepreneurs frequented clubs that offered a refined and exclusive environment for the upwardly mobile. They also offered an opportunity for men to better themselves in the best Victorian self-help tradition. Members discussed politics, conducted business, and used their club’s private libraries for intellectual pursuits or even to attend lectures. Ale, in particular Bass or Allsopp’s IPA, was the drink of choice in the club.

The idea that IPA was a sophisticated, premium, and patriotic drink for an ambitious nation helped it gain market share from traditional ales, particularly in urban areas of the UK. It was the favourite among young people and the middle- and upper-class, who could afford bottled ale to take home. This aspirant class saw traditional ales, with their malty aroma, sweet thick palate, and sometimes warming, high alcohol content, as archaic. They were for stogy geezers, backwards country folk and labourers. Even members of the Temperance Movement, a group who wanted to reduce or even ban alcohol consumption, supported IPA because it was less intoxicating than stout porters, stock ales, and spirits. All this was a bit off-putting for working-class pub goers who felt patronized and couldn’t afford IPA anyway.

The demand for IPA, and their key ingredient hops, was at an all-time high around 1870. Unfortunately for British hops producers a hop blight caused by fungal diseases like downy mildew and powdery mildew hit the UK at the same time. Brewers needed to import hops from Europe and even North America. The result was that IPA now used a blend of hops, creating new flavour combinations.

IPA had become a truly global ale. It had global ingredients, but a ferociously British identity. Marketing had become a key part of the brewing business. The growing middle-class was a huge market and whoever could capture a piece of it would be rich. This is where Michael Bass beat Henry Allsopp.

Bass leveraged technology more quickly and to better effect than Allsopp. By 1870 he was producing roughly four times as much ale. This does not diminish Allsopp’s success, since he was at the same time personally producing twenty-five times more ale than all of Burton-Upon-Trent in the year his father sent his first shipment of IPA to India in 1823. It did, however, allow Bass more time and resources to cultivate the aura of an ideal Victorian gentleman.

There is no reason to doubt that Michael Bass was anything less than the personification of Victorian ideals, nor that he let this go unnoticed. He was a philanthropist who donated public parks, swimming baths, libraries, a church, and a hospital to the people of Burton and Derby, where his business was based. He showcased his innovative brewing technology at world exhibitions, pitching his brewery as a model of British technological advancement. He was also a Member of Parliament for thirty-five years where he helped advance popular causes like the abolition of debtors’ prisons while supporting labourers in their efforts to reduce oppressive working hours.

Bass showed good character in private, too. He worked hard to improve the working conditions of his thousands of employees and turned down offers to become a baron and then a peer, preferring to remain a commoner. His famous red triangle logo, one of the world’s first registered trademarks, was synonymous with quality and British progress. To have a pint of Bass IPA was to hold the best of the modern world in your hand.

That was a tough act to follow. Henry Allsopp was himself an impressive man but in contrast to Bass he was a quiet old-school gentleman from an age that was fading away. Like Bass, Allsopp was a philanthropist but preferred to donate to local charities and infrastructure projects as one donor among several. While it may have been his preference to donate in a less ostentatious way, he was not afraid of status symbols. He became a member of parliament in 1874 and purchased a stately manor home, Hindlip Hall, as a legacy for his family. He accepted a baronetcy upon his retirement from the House of Commons and in 1886 was elevated to the peerage to become the first Baron Hindlip.

Henry Allsopp was a successful and generous family man. He was an ideal citizen of the Old World but his life and brand did not reflect the excitement, progress, and appetite for social change that Victorians craved. It was a brand people were proud of and a part of British history. But it was not a brand for the future and that’s where the aspiring Victorian masses had cast their gaze.

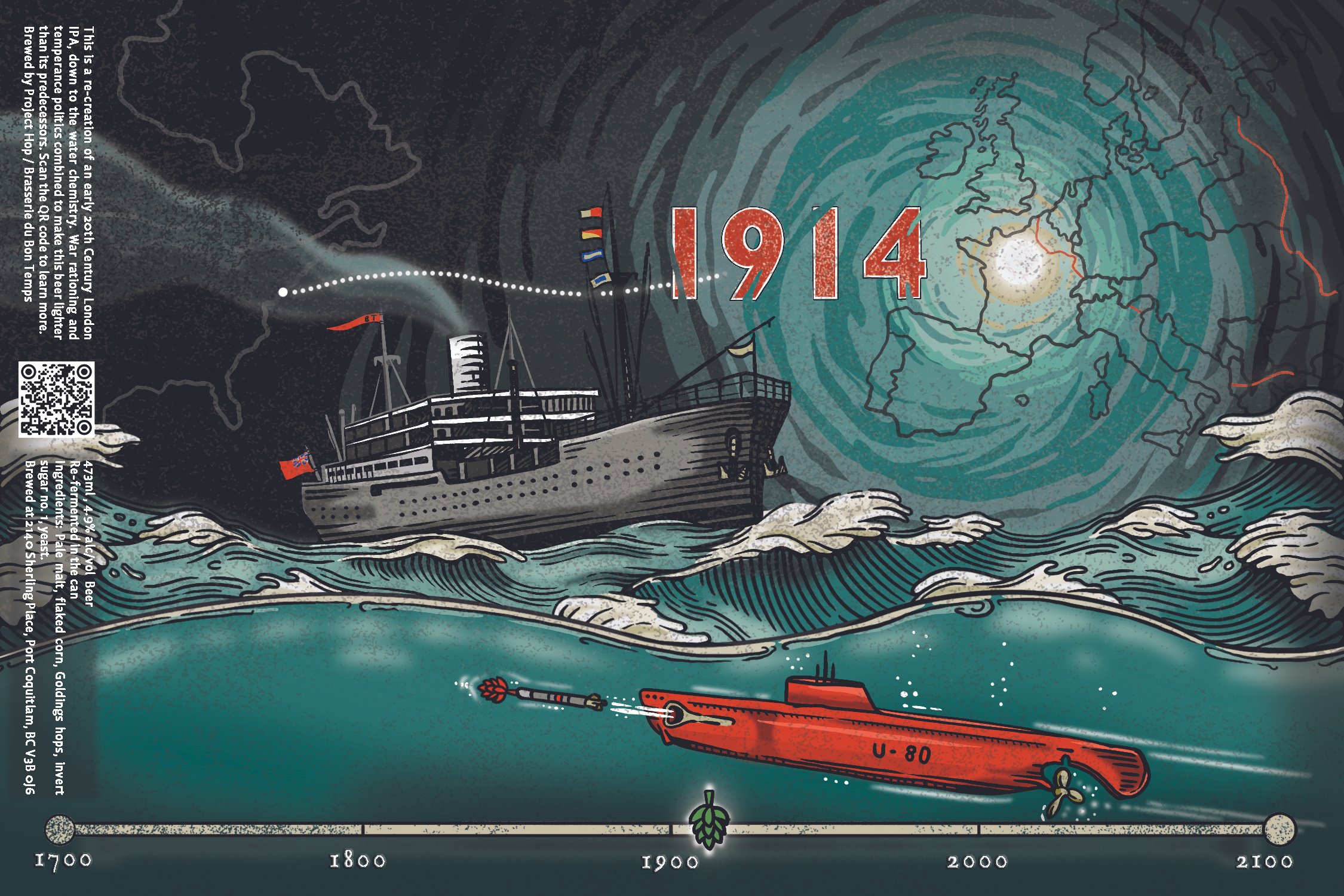

1914: The Changing tastes of a world at war

Dark clouds began to form on the once bright horizon as the British Empire sailed toward the end of the twentieth century. The self-confident Victorian period ended with a pang of uncertainty and tension. A growing awareness of inequality, industrial exploitation, and militarization of empire challenged the long-standing belief in British moral and economic progress.

Doubt and anxiety had taken root in the social consciousness by the early twentieth century. Hope and pride began to fall out of fashion, particularly after the brutality of the Boer War that killed four times as many women and children as enemy combatants. The big, assertive IPA was for a swaggering empire. As that empire’s moral and military dominance waned so too did the ale most closely associated with it.

The humbler pallets of the early 1900’s century began to prefer mild ales and a fashionable new continental style, lager, was gaining popularity in the UK. New taxes on alcohol made these cheaper alternatives to the now even more expensive IPA. Lager, with its sparkling clarity and crisp, clean flavour, had the refined look and feel of an IPA. It also fit the mood, lacking both the in-your-face imperial swagger of IPA and the folksy connotations of mild ale. Lager was for cautious palates that, like cautious minds, sought shelter from the swirling winds of change.

Culture could not keep pace with economic and technological progress. Rapid industrialization created poverty and isolated working people from traditional rural and community ties. It also created decadence and wealth that sheltered the well-to-do from the struggles of most of their compatriots.

The age of machines restructured the work force and stoked fever dreams about dystopian futures where humans lost control of their own creations. Oscar Wilde’s The Picture of Dorian Gray, H.G. Wells’ The Time Machine, and Bram Stoker’s Dracula are famous examples of society’s preoccupation with a degenerate future where the bill for indulgence, moral decay and unchecked technological progress would come due. It wouldn’t take long for reality to write a darker story.

Percy Allsopp, son of Henry and grandson of Samuel, was an early British adopter of lager. Nearly all lager consumed in the UK was imported from Germany and none was brewed domestically. After nearly eighty years of success with his family’s famous IPA he made a bold pivot and switched most of his production to lager. His decision captivated the brewing world.

Percy ordered an expensive, custom-made lager brewery from the United States that integrated the latest advances in brewing technology. His aim was to be the first British brewer to produce lager at-scale, with a planned output of at least 50,000 barrels per year. His grandfather had won massive success with a similar pivot in 1823 when he switched from strong, sweet traditional ales to crisp, bitter IPA in 1823. Percy’s new lager brewery was purchased for £8,000, or £2,900,000 today, and commissioned in 1899. It was a disaster.

The eager eyes of a thirsty public watched as his new equipment failed to perform as planned, causing the loss of early batches to spoilage. Percy was losing money almost as fast as his brand was losing respect. He suffered from bad press, including a newspaper article entitled How to Lose a Million, and resigned in 1900. By 1914 he was bankrupt and the Allsopp family was out of the brewing business six years later.

Bass and other large Bruton breweries including Worthington & Co. and Thomas Salt & Co. continued to produce IPA while also making the traditional darker ales that were slowly regaining popularity. This was not the same world that rewarded brash moves of the kind Samuel Allsopp made in 1823. The cautious wait and see approach other breweries took regarding lager would soon pay off in the most emphatic and terrible way.

The British Empire, the global naval superpower, was locked in an arms race with an ascendant German Empire, now master of the world’s largest army. Britain’s European allies were nervous. Some saw war as the inevitable result of the tension between Britain and Germany. Others thought that globalization had made war so preposterously expensive as to be impossible. All eyes were on Kaiser Wilhem II, an unstable man whose emotions whipsawed between love of his late British grandmother Queen Victoria and hatred of her daughter, his mother, for giving birth to him with a physical deformity.

On July 28, 1914, an assassin’s bullet ended the life of an Austrio-Hungarian prince and shattered a delicate peace. The murder of Frans Ferdinand by a Serbian Nationalist provided an excuse for Wilhem II to invade Belgium. The Pax Britannica was finished. Britain declared war on Germany to defend its ally.

The Imperial Century faded in the haze of artillery fire as the Victorian dream of unlimited progress was replaced by nightmares of the industrial-scale slaughter of early mechanized warfare. This was the year when the best blood of a generation of young European men would begin pour from their shattered corpses and soak into the anguished mire of the Western Front.

German lager was suddenly unpopular in the UK. British styles surged with wartime patriotism and the IPA made a comeback. But it had changed to reflect the times. War rationing restricted the ingredients available. The volume and variety of international goods declined as German U-boats preyed on merchant shipping as part of a strategy to starve the UK into submission.

U-boats hunted in Rudel, or wolfpacks in English. This was a strategy where one U-boat would spot a merchant convoy and trail it at a distance while relaying its position to other submarines. These would all converge on the convoy from different angles, usually at night, and attack in coordinated waves. Many defenseless convoys were annihilated. Those escorted by destroyers hardly fared better. At their peak, U-boat attacks sank 516 ships in a single month.

Ale now needed to be produced with domestic ingredients but there weren’t enough available for traditional recipes. The government had put restrictions on the use of grain to prevent starvation. The IPA dropped from over seven percent alcohol to between three and five percent. Barley malt was so sparse that brewers had to use adjuncts like flaked corn and invert sugar to boot their ales to their new, weaker strength, even when accounting for a massive drop in production overall. U-boats had cut Britain off from its export market, drastically reducing demand for IPA. But IPA wasn’t the British exclusive it used to be.

The New World had developed a taste for hops and was satisfying its own demand. Alexander Keith was making a famous IPA in Nova Scotia. IPA made up three-quarters of John Labatt’s sales in Ontario and Québec the 1890s. The independently minded United States was not as fond of IPA as their Canadian neighbours but still produced some at scale, including Ballantine IPA in New Jersey and Amsdell IPA in New York, the New World’s largest hop growing region at the time.

North America’s massive agricultural prowess meant that New World brewers weren’t affected by marauding U-boats. Still, IPA became light there, too. A hop blight in 1909-1910 combined with the pre-prohibition push for lighter ales in the United States to dial down New World IPA strength to similar levels as on the British Isles. But this blight, the second major disruption to hop supplies in living memory, would plant the seeds of an IPA resurgence a century later.

A hop breeding program at Wye College, London, that had started in 1904 was suddenly interesting across the Atlantic. It was even replicated by other hop breeding programs in Europe and North America. Their initial goal was increased disease resistance but the eventual result would be hundreds of new, highly flavourful and aromatic hops that future generations would one day enjoy.

Britain suffered after its victory in the Great War. It had exhausted its resources defending itself and its allies, and its imperial decline accelerated. Other empires, Austria-Hungary, Germany, and the Ottomans collapsed and were carved-up, while Russia succumbed to paranoid and murderous revolutionaries. The Age of Empire was over.

Britain entered a period of accelerated, but still gradual, social change. Women had entered the workforce while men were fighting overseas. Their work as clerks, factory workers and bus drivers provided a large-scale example of female independence in Britain that had until then only been possible in the colonies. Though men would take back these jobs when they returned from the war, women had emphatically shown they were capable of more than society presumed.

Working class men, whose spilled blood had mixed in the trenches with that of their wealthy compatriots, also gained respect. An act of parliament in 1918 extended voting rights to the male working class and to about forty percent of women. Housing reforms improved the living conditions of the working class beginning in 1919 and unemployment insurance was available in 1920.

Wartime economic disruption had left scars on the economy. Britain’s export market receded along with the disposable income of everyday people. Small breweries had struggled during the war and many larger ones purchased them at a discount once it was over. This was the beginning of what would be a decades-long period of consolidation in the brewing industry.

The big producers were eager to get back to profitability during the 1920s. They leaned-in to the resurgent popularity of the affordable mild ale, producing it at scale and making it even more affordable than it already was. People began to look to the future with hope once more and embrace innovation. Even lager began to make a cautious return to British pubs. The Victorian era was history. As it faded into memory over the next several decades so too would its most famous ale, the IPA.

Though socializing over a pint with men had enhanced women’s autonomy during the colonial period, alcohol had a net-negative effect on women. Men, with their higher tendency to drink excessively and pre-disposition to rowdiness and violence, presented a continued challenge to social and domestic harmony. These dark traits fed on the pain of war and financial insecurity until they stumbled from the shadows and fell before the gaze social reform. Though the early temperance movement advocated a shift from spirits to ale, the woman-dominated early twentieth century incarnation opposed all forms of liquor. The moral logic of temperance and the economic logic of producing cheap ales conspired to create what would be a decades-long trend of light ales.

North America was meanwhile experiencing an industrial and demographic boom. Population doubled between 1890 and 1930 as the once British colonies filled with immigrants from around the world. Canadian breweries suffered from a brief period of prohibition between 1916 and 1918, a result of a combination of temperance politics and wartime grain conservation efforts. Québec repealed prohibition in 1919 and other provinces followed suit throughout the 1920s, creating a regulatory patchwork where only the largest breweries survived. This set off a period of consolidation where, like in the UK, ales became both mass-produced and mild, while small breweries disappeared.

Prohibition was much harsher in the United States. It lasted from 1920 to 1933 at an immediate direct cost of 75,000 jobs in the brewing industry along with thousands of indirect job losses, including the loss of the hop industries of New York State and Vermont. Of the roughly 1,300 breweries in the USA in 1920 only 300 remained operational by the time prohibition was repealed, having survived on the manufacture of sodas and other non-alcoholic beverages. After prohibition the largest breweries underwent a period of consolidation like they did in the UK and Canada, wiping out smaller breweries and producing large quantities of cheap ales.

Very few New World IPAs survived prohibition in the United States, with Ballantine remaining as one of the only examples from the pre-prohibition era. IPA fared much better in Canada, with Alexander Keith continuing to produce at scale, particularly on the East Coast, and Labatt supplying both the French and English markets further west. Some Canadian breweries even supplied ale to the USA in secret while it was outlawed there. But these weren’t the IPAs of old. They were clean, crisp, light ales that resembled slightly hoppier versions of the new dominant global style, lager.

Afterword

The decades that followed would be hard on IPA. It would become a nearly forgotten style until generations later. The craft beer boom would revive the name IPA, but this was a new post-modern incarnation of the classic style. Today’s IPAs are as different form the originals as you are from your great-great-great grandparents.

A new generation of entrepreneurs would reinvent the style in the 1990s. IPA would continue to mirror the society that created it in this, its second life. The rapid pace of the technological age would generate new variants every decade, rather than every fifty-to-seventy years. The fractious, individualist post-modern world of the new Millennium would create off shoots of sub-styles almost annually.

IPA’s journey through mid-twentieth century purgatory and its eventual reincarnation as a trendy ale for a new opulent and anxious age is the focus of the next installment of this story, and of the next mixed pack.

If you enjoyed this story and would like to learn about IPA’s journey through twentieth century purgatory and into its second life as the ubiquitous global style, please let have your say by leaving a comment on this story and subscribing to our newsletter for updates. A comprehensive ten-ale mixed pack and accompanying narrative is in the works. It traces the history of IPA from the pre-Hodgson origin of pale ale, through the present-day sea of craft beer, and into the future to imagine what IPA might be like in the year 2100.

For now, the historical mixed pack is only available in British Columbia (you can order it online here). I’m planning a similar series on porters and stouts, lagers, and ancient/medieval ales. You can stay up to date on new developments via the newsletter.

Teamwork makes the dream work, so if you’re a brewer interested in getting involved in a project to bring the story of ale to your customers, please get in touch. I’d like to get these ales around North America, and that will take some collaboration.

This story is free (sorry, the ale is not). So please pay it forward by sharing this story with someone you think would like it. If this was half as fun to read as it was to write you’ve made my day. All the best, and I’ll be in touch soon.

Nathan Vadeboncoeur,

Brewer at Brasserie du Bon Temps / Project Hop